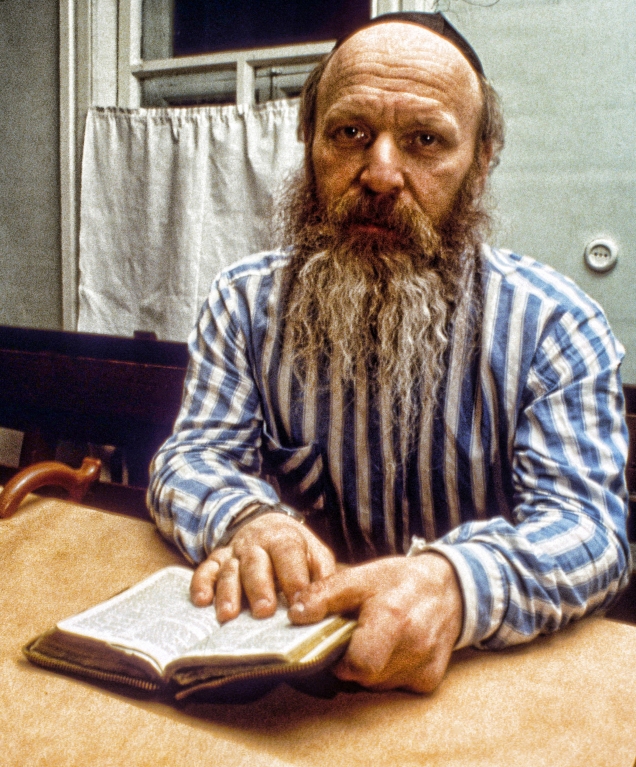

Boris Kaufman, a Sabbotniki. “All the old people have died, and the young generation looks far away. They dislike the place.”

DECEMBER, 1992

BIROBIDZHAN — It’s Friday night in the Jewish Autonomous Region, an area the size of Belgium, planted on swampland in the far eastern corner of Russia. I sit in the region’s only synagogue waiting for Jews. After all, Friday night is the beginning of the Jewish sabbath. But no one shows up tonight, except for the caretaker. And he believes in Jesus Christ. “Some weeks no one comes here,” the caretaker says.

What a strange part of the world this is — Russia’s only official Jewish region. Hardly any Jews live here. Stalin had granted the region autonomy as a Jewish homeland in 1934. Lured by propaganda, which called for young jews to emigrate here and build their own state, seven thousand pioneers arrived and began building a town on the swamp. Many had fled persecution in other parts of the Soviet Union. Later Stalin deported Jews here by force. As he carried out ruthless purges elsewhere, Stalin used the region as a showcase to display his alleged tolerance of ethnic self-determination. In the late 1940s, however, Stalin decided to wipe out everything Jewish in the Jewish region except the facade. In the capital, Birobidzhan, the Jewish street names — like the main boulevard, Shalom Aleichem Street — were allowed to remain. But the schools stopped teaching Yiddish. People stopped celebrating Jewish holidays and attending synagogue. Jewish intellectuals began disappearing to prison camps in Siberia and the Far East. The synagogue hasn’t had a rabbi since the 1960s, and its Torah was stolen several years ago. Without a rabbi or Torah, this simple wooden building can’t even be called a synagogue, only a house of worship. The only worshipers I’ve meet this weekend are Sabbotniki, people who follow the Jewish rituals but believe in Christ. “No one wants to live here,” says the caretaker

A 10-year-old Soviet brochure that Kaufman showed me provides a different story:

“During all the years of existence, not a single resident of the region had been lured by the promises of the Zionists and left the Soviet Union.”

Today, Jews account for less than three percent of the region’s population. Most have left for the new homeland, Israel. Since 1989, 2,400 Jews have emigrated there. The people who remain call these people otyezhanty, Russian slang meaning “those who go away.”

Sophia Brashina, 64, is all packed. She goes away in two weeks. She, her daughter and 168 other Jews from the region are taking a charter flight to Tel Aviv. “I don’t want to go there,” she says. “But I don’t want to be alone. Nearly all my friends have gone to Israel. My son is there, my grandchildren. I’ve lost 10 kilograms just thinking about it. I’m so sad. It’s difficult to change your home place.”

Jews move to Israel because they think economic conditions are better there, she says. But Anna Davydivona Piskovets, 59, who heads the quickly disappearing Jewish Women’s Organization, says many Jews leave because they’re afraid to stay in Russia. “In hard times, people look for an enemy,” she says. “Jewish people are afraid the Russians will find it among the Jews.” Even those who stay have many of their possessions packed so they can leave quickly if they have to, she says.

Ironically, while the Jews are leaving, the new democratic government is working to restore the region’s Jewish identity. The government now funds special concerts on Jewish holidays and recently opened a four-room Jewish school for children to study Jewish history, literature, music and Yiddish. The Great Patriotic War display at the Birobidzhan Museum has been replaced by an exhibit on Stalin’s persecution of Jews. The exhibit’s centerpiece is a long sheet of paper containing hundreds of names. These are the names the Jews from the region who died in Stalin’s camps. The list is still being compiled.

Stalin is dead, the Communist Party is history. The work camps are closed down. So why can’t the Jews feel safe? Why can’t they forget their fears? A few blocks from the museum there’s a building with a hammer and sickle symbol over the entrance. I walk inside. It’s police headquarters for the region. A mural in the lobby features 12 super-sized policemen surrounded by symbols of police power — a helicopter, a police car, a motorcycle, a radio and a club. The men, their faces dark and featureless, tower over a row of apartment buildings. The mural belongs in Birobidzhan Museum as a sarcastic commentary on the abuse of police power. Unfortunately, this is how police see themselves.

“Give me your documents,” says a real policeman. He apparently doesn’t like the way I’m looking at the mural.

I ask if I can photograph the mural. He gets even more upset, and he seems ready to detain me. “Don’t worry, I’m leaving Birobidzhan,” I say, heading out the door.

As I walk down the street, I can see him watching from the window. His face is dark, like the faces in the mural. Now I can understand the fear. If I were a Jew, I’d be on that charter flight to Tel Aviv.