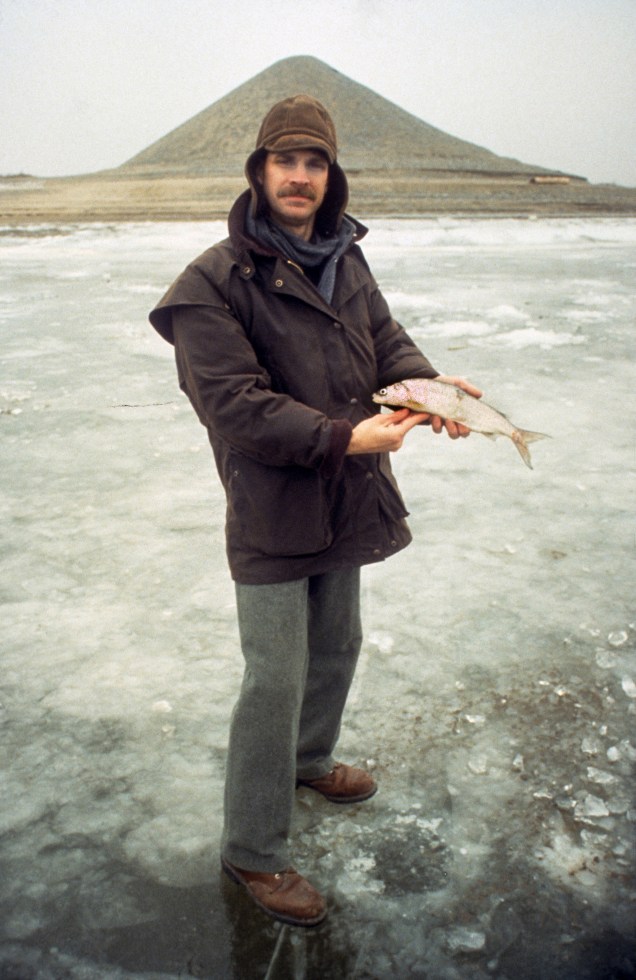

Portraits of some of the residents of Krasny Yar, an Udege village in the Russian Far East.

NOVEMBER, 1992

KRASNY YAR — Amidst the rolling foothills of the Sikhote-Alin Mountains live the Udege people, indigenous Asians who hunt in the one of the most unusual forests in the world — an old-growth taiga that is home for both bears and tigers. Only about 1,500 Udege exist in the world. The largest group lives in Krasny Yar, a village on the Bikin River.

Last week, two American television journalists and I rode ride south from Khabarovsk for six hours on the Trans-Siberian Railway and then rattled up a mountain road in a small bus for four hours. The dirt road came to an end at a swift-moving, ice-clogged river, which we crossed in a narrow wooden boat. On the other side was a village of about 700 people. There aren’t any cars or all-terrain vehicles in Krasny Yar. Except for the distant rumble of the wood-fired boiler at the village school and the voices of children playing in the streets, the village is as serene as the forest that surrounds it.

We went to Krasny Yar to film a short documentary about the dispute between the Udege people and the South Korean conglomerate Hyundai, which wants to log the Udege’s traditional hunting grounds. Environmentalists say logging the area would destroy the habitat of the endangered Ussuri tiger. The Udege say it would destroy their livelihood and culture. Last August, when the villagers heard that logging was about to begin, six Udege hunters took their rifles and flew there by helicopter to guard the trees. Twelve Cossacks from Vladivostok joined forces with the Udege to “defend the border.” Hyundai withdrew the loggers, but the dispute has yet to be settled.

After one night in Krasny Yar, the American journalists and their translator flew by helicopter to Korean logging camps on the other side of the mountain range. There wasn’t any room in the helicopter for me, so they left me behind with the task of guarding the luggage. I was glad to be abandoned. I had grown wearing of the Americans, who bickered constantly. Also, it provided me the chance to learn more about this mountain village.

Although the Udege are an Asian people of the Tungus-Manchurian group, they wear Russian clothes and celebrate Russian holidays. Elders still speak the Udege language, but younger people only speak Russian. Krasny Yar for the most part seems like a typical Russian village. Cows and dogs roam the streets; people busy themselves with rural chores such as chopping wood and fetching water from stone wells.

What makes Krasny Yar unique is its location. No where else in the world is there such a blend of northern and southern plants and animals. Walk in these woods and you might find a spruce entwined by a grape vine, or a Manchurian nut-tree and a Korean pine growing side-by-side with maples and oaks. Northern animals like deer, elk, sable and bear travel the same terrain as wild boars and tigers. This rich diversity can be explained by the climate. Severe, Alaska-style winters are succeeded by summers as luxuriant as in India. The climate here is monsoon, meaning that the prevailing wind changes direction according to the season. In winter, when the wind flows off the frozen steppes of Siberia, temperatures routinely drop to 20 degrees below. In summer, it reverses direction and travels here from the Pacific, bringing with it sub-tropical humidity and heavy rains.

During my stay, I mostly saw just women and children in the village. With the exception of the mayor, some teachers and a few elders, all the men here work in the forest. At the end of October, they travel by boat up the Bikin River to their hunting grounds. They carry slow-moving Russian-made snowmobiles in the boats, and at the end of February, the ride the machines back to the village. Those who have cabins close to the village come back for the New Year’s holiday. They use the snowmobiles only for long-distance travel. When the hunt, they use six-foot-long, seven-inch-wide wooden skis that for traction are covered with deer skin. The men hunt and trap fur-bearing animals, such as sable, fox and mink. For food, they hunt deer and wild boar.

There’s another predator in this forest — the Ussuri tiger, known by Westerners as the Siberian tiger. Typically weighing from 400 to 650 pounds and measuring 9 to 12 feet from head to tail, this tiger is the biggest cat in the world. Its yellowish winter top coat lacks the red stripe of tigers from warmer climates,and its underside, from its face to the back legs and tail, is white. To withstand temperatures that drop as low as 50 degrees below zero, it grows a longer and thicker coat and develops a layer of fat along its flanks and belly. During winter, it must eat over 20 pounds of meat a day to sustain itself.

For centuries, the Udege have worshiped the tiger as a god. To appease it, they place tobacco leaves on its trail. As one Udege man told me, “the tiger and the Udege people are the same.” Unfortunately, in China and Korea, the tigers’ skins, bones and genitals are valued for their medicinal value. Pulverized and used in “tiger wine,” the bones bring about a hundred dollars a pound. It’s against Russian law to kill a tiger, but with the end of the Cold War, Russia’s borders with China and Korea are now open, and poachers have easy access to markets there. After decades of steady growth, the tiger population is now shrinking. Today, there are fewer than 400 tigers, almost all of them living in the narrow stretch of mountains along the Pacific called Sikhote-Alin Range. This same area includes the Udege hunting grounds.

Krasny Yar’s school has a one-room museum containing artifacts of Udege culture: wooden idols, a bow and arrow, a model of a dug-out canoe, a deerskin hat with a feather plume. A painting of a tiger hangs on the wall.

The museum’s caretaker, a reserved man in his 60s, carefully recounted the history of the Udege people. Seven hundred years ago, he told me, the Udege were citizens of the Jurchen Empire, which included parts of present-day China, Mongolia and Russia. The Jurchens had their own written language and agriculture. Archaeologists working in the southern part of Primorski Krai recently unearthed an ancient Jurchen megapolis which included the remains of administrative buildings, fortifications, metal works, moats, towers, a central gateway. The Jurchens had their own written language and a highly-developed system of agriculture. In the 13th century, nomads from the Mongol steppes used scorch earth tactics to destroy the city and crush the empire, The Mongols set fire to the crops and slaughtered the Jurchen people by the thousands. The survivors scattered over the Far East and formed into several small tribes. The people who fled to the Sikhote-Alin mountains eventually became the Udege people. In their isolation, the Udege had developed their own language and customs. To survive, however, they took a step backwards in social evolution and become semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers. They lived in clans along rivers and built squared huts roofed with birch bark and mounted on tripods. They hunted game with spears and bows and arrows and later with rifles.

They lived much like this until the 1930s, when an outside power again forced change upon them. Collectivization was imposed throughout the USSR, and the traditional occupations of native people were organized into producers’ cooperatives. The Communists broke up the Udege clans, gathered everyone into Russian-style villages and set up a hunter/gatherer cooperative. The Udege gave their furs, ginseng, ferns and berries to the government and in return received state wages. While their hunting and gathering tradition survived, most of their other traditions perished. The Soviets prohibited them from speaking their language and worshiping their gods. Shamanism was subjected to mockery by young natives recruited into the Young Communist League. Some shamans fled into the forests and were never seen again. Today, only the elders can speak the Udege language; the middle aged and younger people only remember a few words, such as bugdify, the Udege word for “hello.”

Still, the Udege seemed to have had an easier time adjusting to the modern world than American natives. Communism — an ideology centered on the idea that resources should be shared equally — is closer to the values of Udege culture than capitalism, which prizes competition and individualism. Plus the sheer inefficiency of the communist system has forced the Udege to maintain their barter economy and their reliance on their forest, rivers and gardens for much of their food. Fortunately, the communists had also struck a deal with village leaders to preserve their forest, an area covering 10,000 square miles, or about of the size of New Hampshire. The effect is that the Udege seem to have more self-pride and live more self-sufficiently than most American natives. In oil-rich Alaska, the Eskimos have nicer public buildings, faster snowmobiles, more food in the stores and better medical care than the Udege. Some Alaska natives make more cash in a single day than Udege hunters can earn in a year. But there’s a terrible problem of suicide Alaska, especially among young native men who feel hopelessly displaced in modern America. While Krasny Yar is far poorer, there’s still a role for young, strong men who want to work in the wilderness as their fathers did. I asked several people here if their teenagers ever kill themselves, and everyone had the same reply — never.

With the end of communism, though, some of the same forces that have affected the lives of native Americans have begun to show their influence here. The presence of the mass media is growing stronger. The village practically shuts down when the Western soup operas such as “Santa Barbara” appear on their snowy television screens. At the Friday-night dance at the school, teenagers imitate the rock stars they see on MTV, shown on television every evening for an hour. I’ve noticed that the youngest children, who know almost nothing of the Udege history or language, have managed to memorize the commercials for products like Snickers and Uncle Ben’s ketchup.

If there’s any part of the Udege culture that has survived, it’s the connection with the forest. Now that land in Russia is becoming privatized, who will own the forest? Foreign companies like Hyundai. Russian logging companies? Or the Udege? To be truthful, the Ussuri tiger stands a better chance of being saved from extinction. There are simply too few of Udege and too many Russians. Intermarriage with the Russians and other tribes, a taboo some 50 years ago, has become common place. I was invited to the school one day to watch 12 children dressed in colorful silk ceremonial costumes perform Udege dances. Eleven of the children had round Russian eyes. Only one girl with a beautiful, chubby Asian face seemed fully Udege. I brought her outside for some photographs. She was cold, so I only snapped a couple of pictures. For the whole day after that, all I could think about was that girl. I kept worrying that perhaps I had worked too quickly and had set the wrong exposure on my camera. I wanted to preserve forever the image of the Udege girl standing in the snow.

I waited for four days for the helicopter with the Americans to return, but they never came back. A snow storm had forced them on a detour to Vladivostok. So on the morning of the fifth day, I gathered the luggage and put it on a sled. Andre, the policeman for the region, pulled the sled across the river (it had frozen over during my stay) and loaded the luggage into his truck. Then we began the long drive back to Khabarovsk. After about 20 minutes, Andre stopped the truck and pointed out the window towards the side of the road. He shouted something. I didn’t understand him. I stepped out of the car and walked to where he was pointing. There were tiger prints — two sets — belonging to a mother and her cub. I pressed my palm in the snow and stretched out my fingers. The mother’s print was almost as big as my hand.